Using Bad Publicity to Amplify The MOF’s Influencer Campaign?

For a moment, it seemed the Ministry of Finance (MOF) working with influencers was a stroke of marketing genius… The bad publicity from this decision drew loads of attention to its campaign. That should have turned around the dismal influencer campaign, right?

Wrong… The reach from the bad publicity came a little too late.

MOF Influencer Campaign Causes Uproar

The past weeks has seen Singaporeans deriding the MOF’s decision to use “micro-influencers” in its Budget 2018 campaign.

The influencer campaign sought to reach young Singaporeans and solicit their feedback about the Budget. Since 90 per cent of millennials consume their media online, reaching them through traditional media would have been less effective.

The MOF, thus, hired 50 lifestyle micro-influencers (“opinion-shapers” with 1,000 to 50,000 followers) to drive awareness to millennials about the MOF’s Budget feedback channels. This move created an uproar of mockery and publicity.

#SGBudget2018 got free publicity

Between the mainstream and alternative media, the finance ministry’s influencer brouhaha ranged from sceptical commentary to scathing mockery.

Everyone was doubtful of the influencer campaign’s effectiveness, with a number of critics alluding that the MOF was out-of-touch.

Herein lies the reason why I thought using micro-influencers was genius — by working with micro-influencers, the finance ministry managed to get everyone’s attention. The press, online media, and public went on about it for two weeks — all for free!

How much attention did the mockery drive to Budget 2018?

Exactly how much attention did the uproar drive to the campaign? Was it more than the influencer campaign? And, did the publicity ultimately get millennials to voice their thoughts on the budget?

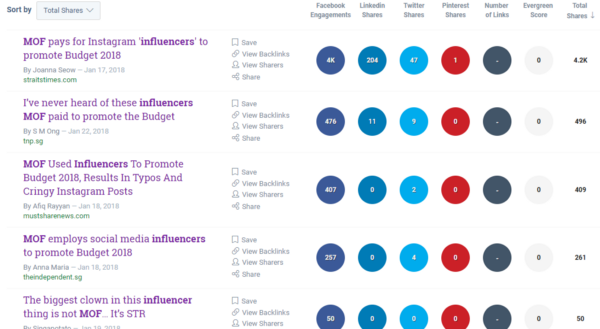

Article Shares on Facebook, Twitter & LinkedIn

I gathered the top 27 articles from Google news, social media, and search results, and ran them through BuzzSumo. The total engagement (shares, likes, and comments) of those articles was 13,258 across Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn.

The bulk of the engagement count came from Facebook — 11,877. LinkedIn and Twitter followed with 936 and 430 shares respectively.

Estimated Article Shares on Dark Social — Email, Whatsapp and other messaging apps

What about the impact of dark social shares? That is — people who shared the articles via Whatsapp, email, or other messaging apps.

Dark social shares are notoriously difficult to track. However, I found Channel News Asia’s (CNA’s) article share count of 13,018 exceedingly insightful. BuzzSumo found the total engagement count to only be 1,339. Where, then, did the rest of 11,679 shares come from?

Assuming that CNA’s counter tracked email shares (and the discrepancy wasn’t because of a bug), this clues us in on how many people shared the news on private channels — nearly 10 times of public engagement counts.

Instagram #notsponsored Satire Posts — mocking the campaign

On Instagram, nearly all the hashtags for the Budget campaign have been hijacked by satire posts (#notsponsored, #unsponsored, and #nonsponsored).

After reviewing all 84 public posts with the official #SGBudget2018 hashtag, I found the following:

- 37 were sponsored by the MOF

- 22 were satire and criticisms

- 22 were posted by the MOF and related institutions

- 2 were neutral

- 1 was an irrelevant hashtag hijack; the content was unrelated to the budget

This means that at least 26 per cent of the posts could be attributed to the uproar. The total likes and comments from these satire posts are 2,521 and 82 respectively.

Although the engagement count (and by extension, reach) for satire posts is far lower than the sponsored posts, they are completely organic — free publicity.

Video #notsponsored posts — mocking the campaign

The most popular public satire video coming out of this uproar is Mr Brown’s sketch — Kim Huat and the Singapore Budget 2018.

Posted on 23 January, the Facebook video has amassed 31,000 views, 776 likes and reacts, 198 shares, and 45 comments thus far. The same video on YouTube has 6,968 views.

For every 38.66 views on the Facebook video, there was one react. For every 56.65 views on the YouTube video, there was one thumb up/down.

The ratio of views-to-engagement gives us an idea of how many people actually watch a video privately without engaging in likes.

What do you think this means for regular articles? How many “silent” readers are there?

Probably fewer than video viewers but significantly more than the engagement count reveals.

What does the engagement data mean?

To be clear, I have used engagement data instead of traffic or reach because the latter two are not publicly available. I have no access to private analytics data and have to rely on public engagement counts to estimate reach.

Indicative of potential reach is the ratio of video views to likes of Mr Brown and CNA’s dark social shares (if it is not a counter bug). In other words, significantly more people have read at least one of the 27 articles but opted not to engage — via likes, shares, or comments.

Thus, albeit negative publicity, people became aware of and were talking about Budget 2018.

So, objective met? Did more millennials respond to the finance ministry’s call for feedback?

No. The publicity failed to get more millennials because…

I wanted to believe that the free publicity helped to amplify the overall campaign (not just the poorly-conceived influencer campaign). However, it did not.

The campaign deadline to send Budget feedback and suggestions was 12 January. The public and social media uproar began on 17 January, five days after the deadline.

This was far too late for the bad publicity to make any impact on its campaign. The MOF had failed to take advantage of the publicity, which would have reached more millennials than the influencer campaign.

Let us dive into the issues with the MOF’s influencer campaign. It would explain how crucial it was for the finance ministry to leverage the publicity it got.

Did The Influencer Campaign Do That Badly?

According to MOF’s spokesperson, it estimated that its influencer campaign would reach 225,000 Instagram followers. Let us assume that Instagram reach is its KPI (Key Performance Indicator).

Now, reach in Instagram analytics measures the number of unique people who have seen a post.

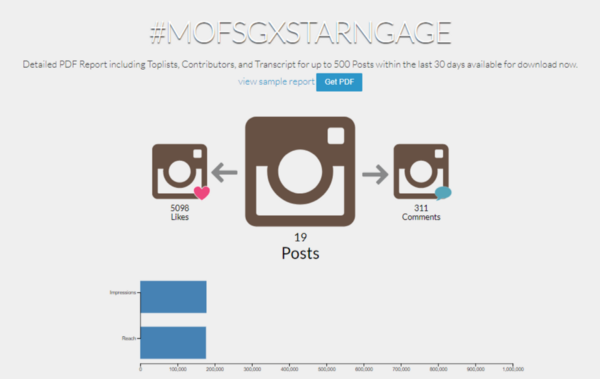

Instagram Reach via Hash Tracking

While we cannot access private Instagram analytics for each influencer to determine exact reach, Hash Tracking provides a close estimate.

The hashtag #MOFSGxStarNgage reached roughly 180,000 people with 19 posts. One of the posts is a satire post with immaterially low engagement. As such, there is no need to adjust the total reach to reflect its immaterial impact.

The rest of the 18 posts are MOF-sponsored.

Although 180,000 is below the ministry’s estimate, we have to consider other influencer posts that are not captured by this hashtag. After all, there are roughly 50 influencers hired for this campaign. We have only seen the reach of 18 sponsored posts.

Looking at the official hashtag #SGBudget2018, the reach comes close to 500,000. But, only 37 out of the 84 posts are MOF-sponsored.

To get an accurate approximation of reach, we prorate the total reach by the distribution of likes. Since the 37 sponsored posts generated 11,912 out of 14,763 total likes, sponsored reach is roughly 400,000 — far better than the MOF’s estimate of 225,000.

Note: I will release the spreadsheet with the engagement data soon.

So, pretty good? The MOF met and exceeded its KPI.

No. Here is the problem…

Problems with the Influencer Campaign

Influencer marketing works. But, it has to fit the campaign. This campaign, unfortunately, does not fit the MOF’s objective.

#1 — Instagram reach is an inappropriate metric/KPI

Using reach as a success metric is meaningless for the influencer campaign.

The average person scrolls through Instagram without reading captions, especially long ones with awkward copies. Yet, the MOF’s campaign relied on Instagram captions to convey its solicitation of feedback.

No one, who saw only the photos, would know this.

A better KPI would be the total Singaporean traffic from all the influencers’ campaign links. Unfortunately, this is data that we do not have.

Disclaimer: We do not know if the MOF is using reach as its campaign KPI.

#2 — MOF Influencers’ followers may not have been audited

Whenever you embark on a social media campaign, you need to do a social media audit.

One relevant audit is whether an influencer’s followers are representative of a campaign’s intended audience. Another check to conduct is whether the followers are organically grown or fraudulently bought. A graph of follower growth showing unexplained steep spikes would suggest an influencer has bought followers.

Popular Chips Daily identified that the top four MOF influencers have at least 65 per cent of their followers from Singapore, which is acceptable. However, it also pointed out that one influencer had as low as 8.32 per cent of their followers from Singapore. Why, then, was he or she picked? It lowers the actual reach to Singaporeans — MOF’s target location.

Furthermore, Popular Chips Daily found the same influencer’s geographic follower ratio unusual, which may suggest the influencer bought followers. This further undermines actual reach.

#3 — No Connection between Lifestyle and Finance

Wesley Gunter, wrote on Mumbrella about the astonishing lack of connection in the MOF’s influencer campaign. The lifestyle influencers picked are a wrong fit mainly because they do not appeal to the average millennial. Moreover, the bulk of their followers are unlikely to respond to the budget campaign.

This would mean far fewer people voicing their thoughts at the MOF’s listening points and on online feedback channels.

#4 — Instagram is not the best channel for this campaign

People scrolling through their Instagram feed are not primed to give their views on financial policy. They are there to see aesthetically pleasing photos. This is evident in the comments of the sponsored posts — mostly complimenting the influencer on their looks or romance.

Moreover, the photo-oriented platform with truncated captions does not do justice to the MOF’s campaign message.

One indicator of this is Popular Daily Chip’s finding on engagement. In its article, it found that the MOF sponsored posts were doing 5.4 per cent worse than the influencers’ regular sponsored posts.

Instead, influencers and thought leaders on platforms like YouTube, blogs, and even Facebook may deliver a better conversion rate than Instagram. A video message or blog post would better deliver the budget feedback message than a truncated Instagram caption.

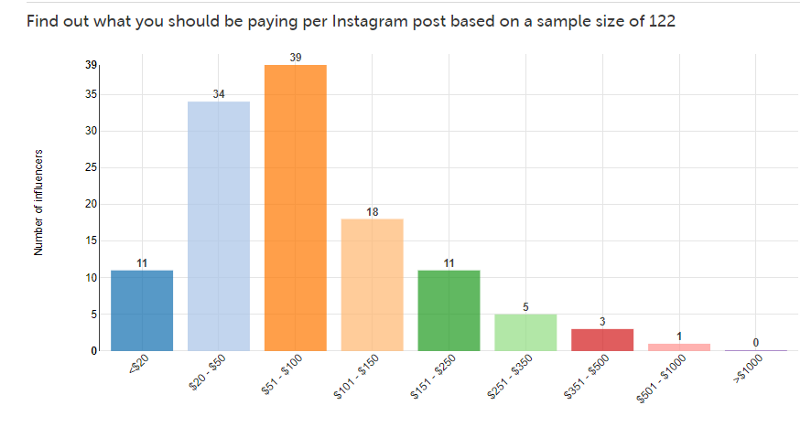

How much does the present influencer campaign cost?

Based on the market rate chart by StarNgage (the platform where the MOF got its influencers from), each micro-influencer costs between S$20 to S$150. I have set the minimum potential reach for each influencer at 5,000+ in consideration for the MOF’s estimated 225,000 reaches.

That means the budget range of the MOF is between S$1,100 to S$8,250 for 50 micro-influencers. The cost includes a 10 per cent commission to StarNgage.

So, how did the influencer campaign really do?

We have no hard numbers from the MOF’s private analytics to go by. At the same time, reach is a terrible metric to measure success.

But, the four issues significantly undermines the influencer campaign’s effectiveness, even though the experimental campaign can cost as low as S$1,100.

Read Westley Gunter’s article for a better idea of why the MOF influencer campaign was terrible.

In that case, should the MOF have used the bad publicity to amplify the overall budget campaign, which included promotional videos and official social media posts?

Take advantage of the influencer backlash!

The uproar seemed to drive far more relevant attention to the Budget than the influencer campaign itself.

So, why not announce the decision to work with influencers during the third quarter of last year? This would bring forward the criticisms to the fourth quarter of 2017, early enough to divert attention to the Budget 2018 microsite before its deadline.

But…is negative publicity, good publicity?

The 2010 study, Positive Effects of Negative Publicity: When Negative Reviews Increase Sales, suggests that negative publicity can drive awareness to a campaign that is relatively unknown.

To quantify the positive effect — negative reviews increased sales of books by unknown authors by 45 per cent. The bad reviews drove attention to books that would otherwise have been left unnoticed. That is the key point we want to focus on — draw attention to the campaign, which would otherwise have gone unnoticed.

Further, the University of Pennsylvania study in 2011 found that the sleeper effect meant people eventually forgot their initial bad impression from negative publicity.

That is why it is relatively harmless for the MOF to use the mockery to draw attention to its feedback channels.

But, should a government institution even use bad publicity? Wouldn’t it undermine public confidence?

There are indeed disadvantages of being embroiled in bad publicity. These include loss of trust (public confidence), damaged brand equity, and damaged brand association.

However, the mockery of the MOF’s influencer campaign does not undermine public confidence. Neither does it damage brand equity nor the association of the government.

For a monumental example of negative publicity that destroys all three, refer to the 1MDB scandal.

At the same time, there are varying extents of negative publicity. The decision to work with influencers is in no way similar to a corruption scandal.

The public, at most, sees the MOF as out-of-touch with young Singaporeans, which is a common perception in other nations. The alternative media frames it as a waste of taxpayers’ money.

Nothing that serious.

Wait! Isn’t being seen as out-of-touch bad?

Then, why did the MOF work with lifestyle micro-influencers in the first place?

By choosing to hire lifestyle influencers, the uproar was sure to happen. There was no avoiding it at all.

After all, the average Singaporean does not understand the concept of influencer marketing and has a distaste for lifestyle influencers. The MOF should have expected the brouhaha, especially after the FavesAsia and SGInstababes furores in 2017.

If the MOF did not want to handle bad publicity, it should have engaged a competent marketing agency to reach its core audience — millennials who cared enough to give feedback. Yet, it chose to move ahead with the influencer campaign.

And, I applaud the MOF for taking that risk. Marketing policy feedback to millennials, who are somewhat politically apathetic, is notoriously difficult.

Nonetheless, this fact remains — the MOF’s only option, due to its decision, is to anticipate the uproar and mitigate the bad publicity. Its bonus move is to use the brouhaha to its advantage and reach its campaign objectives.

Why not do both?

To clarify, I am not suggesting that the finance ministry orchestrate a controversy like how the White Moose Cafe has done with a British influencer. That would indeed undermine public confidence and alienate portions of the population — a strategy that may work for niche businesses but not for a government institution (that serves the public).

How to use mockery to amplify the Budget campaign?

At this point, we need to be clear that the influencer campaign is a smaller subset of an overarching marketing strategy. Other than working with influencers, the MOF has been actively promoting the budget on YouTube and its official social networks.

Our objective is to divert attention directly to the REACH microsite, videos, and official social media posts. Trying to amplify a poorly conceived influencer campaign is a waste of resources.

To put it bluntly, the influencers are fodder to get the media talking. Then, we “taichi” (divert) the attention from them.

Step 1 — Anticipate the backlash and make it happen earlier

As early as September 2017, the MOF should have released a press release announcing its intention to experiment with influencer marketing. It should convey its desire to reach young Singaporeans and provide information (and links) on how the public could share their thoughts about Budget 2018.

With the timing of the press release just months after two influencer furores, the media’s report would have a heavier slant towards scepticism. The public will pick the articles up and mock the decision.

Yet, by explaining the rationale of the decision, the MOF paves the way for online “debates”. This would drive the first wave of publicity to the Budget campaign.

Step 2 — Refine the Influencer Campaign & Hire a Diverse Group of Influencers

In October 2017, the MOF should hire influencers who are relevant to millennials; people whose ideas millennials respect (for instance “micro” thought-leaders in entrepreneurship, business, and personal finance rather than lifestyle).

It should also consider influencers on other platforms — YouTube and blogs. As explained, Instagram is not the best place to market policy. Photo captions also fail to convey the Budget 2018 message well.

That said, the MOF should still work with a select few lifestyle influencers who can drive results. Only one of the influencers in the present campaign garnered mostly relevant comments to the Budget.

Lifestyle or not, the MOF should audit all of its influencers to ensure most of their followers are Singaporean and legitimate.

By the end of October, the news would have “leaked out” and the second wave of publicity will begin brewing.

Step 3 — Mitigate the effects of bad publicity and create the second wave of publicity

Before November 2017, confirm to the media that the influencers have been hired. Then, soak in the full extent of the publicity from the mainstream and alternative press, and online media publishers.

With the influencer campaign refined, respond to journalists and sceptics with the updated plan and link to the campaign’s microsite (REACH). Back it with facts and data. This mitigates the negativity, galvanises support from both the public and influencer community, and draws attention to the campaign microsite.

Step 4 — Reshare influencer posts and draw attention

Finally, begin the influencer posts in December, which draw attention to the physical avenues for millennial to share their thoughts. Then, share a few influencers’ posts on its official social media channels.

Sceptics and critics would invariably want to evaluate the effectiveness of the posts. In doing so, they will inadvertently come to know about the policy feedback channels.

This is also when the third wave of mockery (and support) will develop, especially toward the lifestyle micro-influencers.

Results of Riding Three Waves of Publicity

Because of the three waves of publicity, there will be a significant increase (more than what has already happened) in satire Instagram posts and YouTube videos. People will post their thoughts on the MOF’s decision to use influencers.

When we prolong the virality of MOF’s decision, through waves, the media has more time to churn out stories. More Singaporean YouTubers and thought leaders will weigh in on the issue.

The alternative media will, undoubtedly, continue its criticisms. But, with the steps taken to mitigate the negativity, there will be supporters.

This encourages an online debate that has an effect on social media algorithm. Facebook’s algorithm would likely prioritize posts that mention Budget 2018 and influencers within Singapore.

This combination should magnify the campaign’s reach (not Instagram reach) significantly and encourage more millennials to voice their thoughts on the government budget.

By the deadline of 12 January 2018, the MOF would have gotten significantly more attention (than it presently has) by taking advantage of and mitigating the public mockery.

Is this the best marketing strategy?

No. Of course not.

But, it complements the overall budget campaign and uses the influencer campaign as fodder to amplify reach.

Should the MOF choose to refine its influencer campaign and work with relevant thought leaders outside of Instagram, the marketing cost will inevitably rise. However, it would be better able to reach its intended audience.

Bottomline

The present influencer campaign seems to be ineffective. The use of reach as a metric is meaningless. There is also a mismatch between lifestyle influencers and the MOF’s message.

For the best results, engage a marketing agency that knows what it is doing and has the ability to manage an effective campaign — influencer-related or not.

Otherwise, take advantage of the bad publicity to amplify the existing campaign, and mitigate its negative effects.

Let me know what you think.